A great deal of ink has been spilled recently about the economic meltdown in Cyprus. The latest domino in the slow collapse of the European monetary union, Cyprus introduced radical solutions to meet the demands of the EU (European Union) and International Monetary Fund (IMF). Now, Cypriot bank depositors have lost chunks of their savings, the Cyprus government has imposed currency controls, and the central bank may be forced to sell the majority of its gold reserves. In some ways, however, the Cypriots are receiving a better deal than citizens of the U.S., U.K., or Canada.

The Cyprus bank crisis is intimately tied to that of Greece. Due to rising unemployment and benefit payments, the volume of state debt – much of which is funded through Greek loans – steeply increased during the recession. In order to fund the loans, Cypriot banks bought Greek bonds. As a result of the Greek bailout settlement, the bonds suffered a 50% haircut, in turn threatening the collapse of the Cypriot banking sector.

Fast forward to 2013 and, unable to fund a bailout of local banks based on tax revenues or savings, Cyprus turned to the EU for assistance. In came the “troika” – the European Central Bank, European Commission, and the International Monetary Fund – to begin negotiations and lay down terms. The final deal would require Cyprus to impose strict austerity measures and raise €4.2 billion in return for a €10 billion loan to the insolvent Cypriot banks. The second largest bank country, the Cyprus Popular Bank, will be shuttered as it is combined with the single largest bank. Too big to fail at it’s finest.

The initial package included a remarkable provision requiring the confiscation of 6.7% of all accounts under €100,000 (the insurance limit for deposits) and 9.9% of all accounts over the threshold. As citizens rioted in protest, the Cypriot parliament overwhelmingly rejected the package. A new Deal, which the Cypress parliament has still to approve, dropped the levy on accounts up to €100,000 but increased it to 40% on accounts over €100,000. In return for their kind investment, high balance account holders will receive bank shares (of dubious future value) in the amount of the levy.

To combat capital flight out of banks in advance of the levy, Cyprus limited withdrawals on the island to €260 per day and closed local banks for two weeks. Branches in Russia, Greece and London Remained Open, allowing most Russian, U.K. and EU citizen cash safe exit prior to the confiscation. Withdrawal limits continue, and those leaving the island may take no more than €1000 in cash with them.

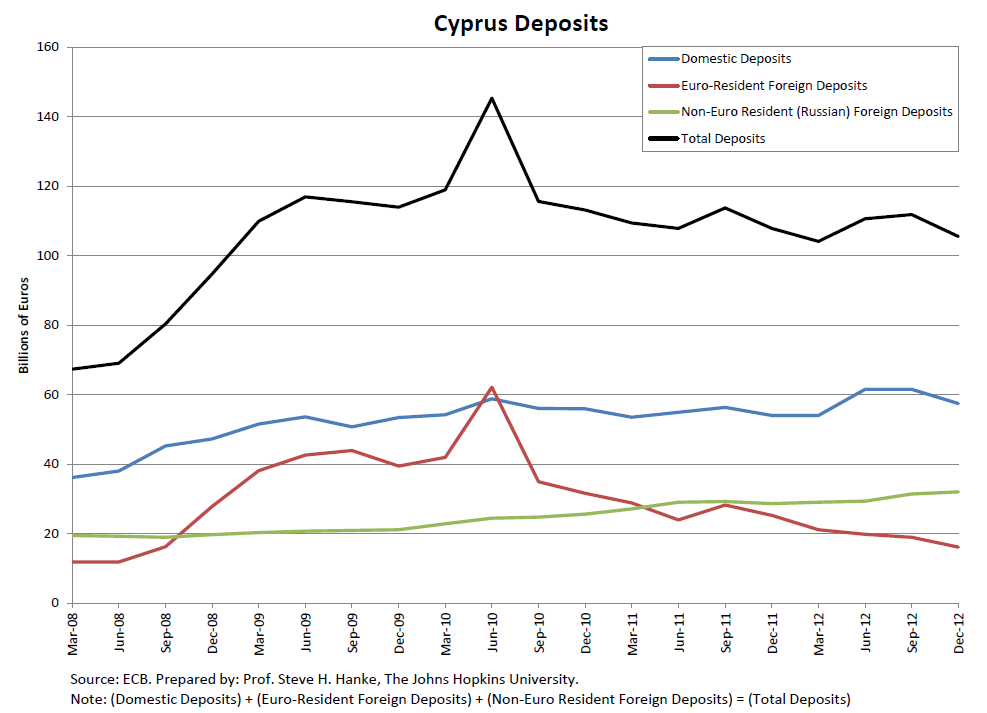

To update the chart above, on March 21 JP Morgan reported there is €21b remaining in non-Euro resident accounts, comprised of 80% Russian and 20% U.K. resident deposits (the green line). JP Morgan added that Euro-resident deposits had fallen to $5b. The lockdown was botched.

The spectacle of deposit confiscation – euphemistically named a “bail in” – shocked individuals worldwide but had been planned by central bankers for some time. In January, the Swiss government announced changes to banking Rules allowing confiscation to recapitalize failing Swiss banks. The European Commission has introduced a law to formalize confiscation of deposits over €100,000 in any failing bank, despite it being common practice globally not to insure large deposits. In typical Euro-speak, a spokesperson Confirmed this: “In the Commission’s proposal, which is under discussion, it is not excluded that deposits over 100,000 euros could be instruments eligible for bail-in.”

Lest those outside Switzerland and the Eurozone breathe a sigh of relief, policies are already in place in the U.S., Canada, New Zealand and the U. K. In a December 2012 joint Paper, the FDIC and Bank of England outline plans to confiscate deposits during the next banking crisis rather than pursue another unpopular taxpayer-funded bailout. Jim Flaherty, the Canadian Finance Minister, slipped Hints into the budget bill that Canada would pursue the same path to rescue any large failing banks. New Zealand implemented a similar Scheme in March.

Nor is the fate of the biggest deposit in the Bank of Cyprus safe from the bailout package. The central bank holds 13.9 metric tons of gold. Though independent of government control, the Bank of Cyprus is under troika pressure to sell 70% of the nation’s gold reserve. This marks the first time during the Eurozone crisis that gold sales have constituted part of a bailout agreement – the gold of Greece sits as Collateral for the loan package, but remains untouched. In defiance of the central bank the Cypriot Government stated they are considering a gold sale within the next few months, while the European Central Bank Expects the proceeds of such a sale as reimbursement for emergency loans.

The governor of the Cypriot central bank bitterly resents local political pressure, Telling reporters: “The independence of the central bank of Cyprus is being attacked at this time.” As always in a crisis, one watches to see who the winners and losers will be. Greece’s gold may be forfeit, and now Cypress’s, as the Eurozone dominos fall. Who are the likely buyers of all this new debt that ensures older ECB’s loans are repaid? At the end of the day the same central banks printing, are buying this debt, exacerbating the circular process. At the end of the day those holding the most gold win.

In some respects, the Cyprus package is a forward-looking approach. With the threat of confiscation in the event of bank collapse, depositors have an incentive to scrutinize bank health and policies. Only the strongest banks will attract deposits. Moreover, bail in restores a level of moral hazard back to bankers.

Direct theft by banks is a fairer policy than the Fed’s current war on savers. The gap between interest rates and inflation of prices eats away at family savings. As one Forbes Magazinecommentator states, “Without any authorizing legislation, the U.S. government has quietly confiscated more value than Cyprus. With a long-term annual inflation of approximately 4.1% and only a 1% annual interest rate, your assets are guaranteed to lose value over time.” Should U.S. bank depositors eventually be forced to bankroll the banking sector, the theft would be more brazen but arguably no worse. Cash has become a risky long-term investment, a reminder that banks are best used for short-term transactions only.